Moral and Ethical Pursuit of Profit

Exogenous factors put enormous pressures on small farmers, and the success of the small farm can ultimately be predicated on the ability of owners to manage these pressures. Management strategies such as the business plan and budgeting play a large role as preemptive measures on the financial side; however there are many other forces, issues, and many unforeseen elements that must be dealt with. It is important to emphasize that although these subjects invariably all have serious financial ramifications, they go well beyond the discussion of money. Making money (profit) while simultaneously adhering to legal, moral, and social obligations can present unique challenges that must be filtered through many different lenses.The weight and complexity of having to make these everyday decisions can be enormous. As environmentally-friendly and socially-conscience practices meet the onus the farmer has to society at large, they can also be a key component of a good and economically sound business plan. The new paradigm small farm model will above all else, prove that :

Making a fair profit and conducting business in a moral and socially responsible manner are not mutually exclusive pracitices but, in fact, synergistic.

Exogenous factors put enormous pressures on small farmers, and the success of the small farm can ultimately be predicated on the ability of owners to manage these pressures. Management strategies such as the business plan and budgeting play a large role as preemptive measures on the financial side; however there are many other forces, issues, and many unforeseen elements that must be dealt with. It is important to emphasize that although these subjects invariably all have serious financial ramifications, they go well beyond the discussion of money. Making money (profit) while simultaneously adhering to legal, moral, and social obligations can present unique challenges that must be filtered through many different lenses.The weight and complexity of having to make these everyday decisions can be enormous. As environmentally-friendly and socially-conscience practices meet the onus the farmer has to society at large, they can also be a key component of a good and economically sound business plan. The new paradigm small farm model will above all else, prove that :

Making a fair profit and conducting business in a moral and socially responsible manner are not mutually exclusive pracitices but, in fact, synergistic.

The Farm Labor Dilemna and Ineffectual, Unrealistic Immigration Policies

The pressures of planting and harvesting deadlines are often complicated by factors such as market opportunities and the weather. In all but the most mechanized of farming operations the availibilty of skilled hand-labor determines the success or failure and often the size of profit margins during these crucial operations. The temptation/necessity to complete these operations at any cost, which includes hiring of undocumented workers, may seem rational in the short term but can be a risky strategy with many negative ramifications. As a member of a lawful society and one that benefits from that society, there are written and implied rules of conduct and fiscal responsibilities that must be followed. While often the rules may be perceived to be unfair and stacked against the small business owner, he is bound both legally and morally to adhere to these rules. This is true in even in the case of undocumented workers who utilize infrastructure, educational resources, and often, as a matter of survival, certain government aid and medical assistance, the cost of which is beyond their means. The Congressional Budget Office calculated that the federal government’s contribution to the healthcare and education of illegal immigrants in fiscal year 2006 amounted to a figure in excess of $1 billion while state budget share ranged from a low of a few million(states with a minor unauthorized population) to a high of over $10 billion in California. In real terms, this data supports claims that the costs associated with the health and welfare of illegal immigrants in California alone average about $1100/yr. in additional taxes for the average household in that state. (1) (2)

The pressures of planting and harvesting deadlines are often complicated by factors such as market opportunities and the weather. In all but the most mechanized of farming operations the availibilty of skilled hand-labor determines the success or failure and often the size of profit margins during these crucial operations. The temptation/necessity to complete these operations at any cost, which includes hiring of undocumented workers, may seem rational in the short term but can be a risky strategy with many negative ramifications. As a member of a lawful society and one that benefits from that society, there are written and implied rules of conduct and fiscal responsibilities that must be followed. While often the rules may be perceived to be unfair and stacked against the small business owner, he is bound both legally and morally to adhere to these rules. This is true in even in the case of undocumented workers who utilize infrastructure, educational resources, and often, as a matter of survival, certain government aid and medical assistance, the cost of which is beyond their means. The Congressional Budget Office calculated that the federal government’s contribution to the healthcare and education of illegal immigrants in fiscal year 2006 amounted to a figure in excess of $1 billion while state budget share ranged from a low of a few million(states with a minor unauthorized population) to a high of over $10 billion in California. In real terms, this data supports claims that the costs associated with the health and welfare of illegal immigrants in California alone average about $1100/yr. in additional taxes for the average household in that state. (1) (2)

Pay Scales and the Minimum Wage

Throughout the history, and to the present day, low wage earners have been exploited because of their inability to afford to defend themselves and their fear of losing their meager livelihood. Paying less than the minimum wage has a wide-range of implications that, beyond the obvious legal ramifications, go to social and quality-of-life issues. One of the first considerations in this discussion should be: what is “reasonable compensation” for the work that is performed, allowing for a fair profit for the grower while enabling the worker to reap a margin that is greater than the cost of mere survival. By definition, this margin-plus-survival threshold is termed a living wage, but when put under scrutiny is no more than an amount that meets basic needs and provides some ability to deal with contingencies like minor medical emergencies sans an influx of government assistance. That defined, a Harvard study reports that the living wage threshold actually is “considerably higher” than the federal minimum wage ($7.25/hr.), which itself does not approach any realistic number that meets the basic needs of working-class people in any region of the country. As an example, a single parent with one child, earning minimum wage, working 40 hours per week, will eke out an existence that meets the federal poverty level of $14,710 with just $370 to spare but when housing and other basic necessities are calculated (the “living wage”) this number falls short by, at minimum $2392, in rural and small to medium urban areas.Though “quality of life” issues involve an individual’s perception of his position within in his environment beyond money ( level of self-satisfaction, self-worth and comfort), the inability to afford anything beyond the basic necessities for survival seriously erodes this perception. The perception of a low-quality of life that includes diminished self-worth can contribute greatly to societal ills like crime, and drug abuse. Seemingly small actions, when multiplied within a societal structure can geometrically increase to effect society-at-large in a big way.(3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

Throughout the history, and to the present day, low wage earners have been exploited because of their inability to afford to defend themselves and their fear of losing their meager livelihood. Paying less than the minimum wage has a wide-range of implications that, beyond the obvious legal ramifications, go to social and quality-of-life issues. One of the first considerations in this discussion should be: what is “reasonable compensation” for the work that is performed, allowing for a fair profit for the grower while enabling the worker to reap a margin that is greater than the cost of mere survival. By definition, this margin-plus-survival threshold is termed a living wage, but when put under scrutiny is no more than an amount that meets basic needs and provides some ability to deal with contingencies like minor medical emergencies sans an influx of government assistance. That defined, a Harvard study reports that the living wage threshold actually is “considerably higher” than the federal minimum wage ($7.25/hr.), which itself does not approach any realistic number that meets the basic needs of working-class people in any region of the country. As an example, a single parent with one child, earning minimum wage, working 40 hours per week, will eke out an existence that meets the federal poverty level of $14,710 with just $370 to spare but when housing and other basic necessities are calculated (the “living wage”) this number falls short by, at minimum $2392, in rural and small to medium urban areas.Though “quality of life” issues involve an individual’s perception of his position within in his environment beyond money ( level of self-satisfaction, self-worth and comfort), the inability to afford anything beyond the basic necessities for survival seriously erodes this perception. The perception of a low-quality of life that includes diminished self-worth can contribute greatly to societal ills like crime, and drug abuse. Seemingly small actions, when multiplied within a societal structure can geometrically increase to effect society-at-large in a big way.(3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

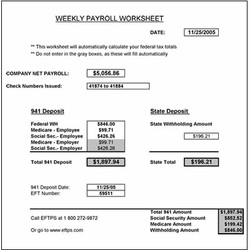

Payroll Taxes and Workman's Compensation : Cash Killers, but an Obligation.

From matching state and local tax contributions to workman's compentiation fees, these mandated policies can be a burden like no other to the small to medium farmer that must hire outside help to survive. not paying matching withholding taxes, Workmen’s Compensation insurance fees, or unemployment benefits for these workers are all crimes under the law. Failure to pay these required fees can result in not only civil penalties and fines, but also, in severe cases, the real possibility of criminal penalties that can result in jail time. [The IRS incarcerated 117 individuals since 2007 with an average sentence of 17 months] Of all the consequences discussed, these are indeed the ones that have the most immediate impact because they can be discovered with just a shred of forensic evidence. This easy-to-discover evidence can run the gamut of unusual cash expenditures during times of high labor-demand such as harvests and planting to payrolls that don’t balance well with periods of large receipts and bank deposits to testimony from a disgruntled employee, or to, as often is the case, sloppy accounting and record keeping. Beyond the social stigma and the complications that accompany a criminal record, comes the stark and harsh reality in terms of costs of fines and penalties. Tax fraud penalties can result in fines of tens of thousands of dollars, seizure of property, and liens not just on company property but also the personal property of those who the IRS deems complicit in the fraud. Additionally, after the principle of any past due withholding taxes have been remitted to the IRS, a failure-to-pay penalty is assessed at one-half of one-percent of the of the unpaid tax for every month or part of month after the due date of unpaid taxes; a figure that can sap significant dollars from the cash flow of any small business. Adding to the failure-to-pay penalty is the failure-to–file penalty which is 5% of the unpaid tax return for each month, or part of month, the return is late. While IRS audits are rare, sophisticated computer profiling systems such as the Discriminant Function System (DIF) and Unreported Income (UIDIF) programs utilized by the agency can detect nuanced anomalies that can trigger scrutiny that extends beyond the year that the original violation(s) occur.Discounting all moral and ethical considerations, and utilizing the most basic interpretation of good business practices, tax avoidance for short term gains or to solve cash flow problems is an unworkable and costly strategy. (8) (9)

From matching state and local tax contributions to workman's compentiation fees, these mandated policies can be a burden like no other to the small to medium farmer that must hire outside help to survive. not paying matching withholding taxes, Workmen’s Compensation insurance fees, or unemployment benefits for these workers are all crimes under the law. Failure to pay these required fees can result in not only civil penalties and fines, but also, in severe cases, the real possibility of criminal penalties that can result in jail time. [The IRS incarcerated 117 individuals since 2007 with an average sentence of 17 months] Of all the consequences discussed, these are indeed the ones that have the most immediate impact because they can be discovered with just a shred of forensic evidence. This easy-to-discover evidence can run the gamut of unusual cash expenditures during times of high labor-demand such as harvests and planting to payrolls that don’t balance well with periods of large receipts and bank deposits to testimony from a disgruntled employee, or to, as often is the case, sloppy accounting and record keeping. Beyond the social stigma and the complications that accompany a criminal record, comes the stark and harsh reality in terms of costs of fines and penalties. Tax fraud penalties can result in fines of tens of thousands of dollars, seizure of property, and liens not just on company property but also the personal property of those who the IRS deems complicit in the fraud. Additionally, after the principle of any past due withholding taxes have been remitted to the IRS, a failure-to-pay penalty is assessed at one-half of one-percent of the of the unpaid tax for every month or part of month after the due date of unpaid taxes; a figure that can sap significant dollars from the cash flow of any small business. Adding to the failure-to-pay penalty is the failure-to–file penalty which is 5% of the unpaid tax return for each month, or part of month, the return is late. While IRS audits are rare, sophisticated computer profiling systems such as the Discriminant Function System (DIF) and Unreported Income (UIDIF) programs utilized by the agency can detect nuanced anomalies that can trigger scrutiny that extends beyond the year that the original violation(s) occur.Discounting all moral and ethical considerations, and utilizing the most basic interpretation of good business practices, tax avoidance for short term gains or to solve cash flow problems is an unworkable and costly strategy. (8) (9)

Moving Beyond Dollars and Cents

The Whole World is Watching: Global is Local.

In the new global economy, business ethics extend well beyond the “dollars and cents”parameters of what was once the way all business was conducted. New business paradigms have shifted to include the requisite importance of integrating social and environmental considerations into any modern business model. [It is important to note that not even the small farm exists outside the global economy. As morality and altruism should, and do, play a large role in this type of “business thinking” in the long term (as these considerations become part of the norm), they will also make good economic sense in terms of the bottom line. [Modernized shipping methods and the internet (especially in the realm of market access/pricing/product quality) has made all farming “local.”] A company or a farm’s reputation (image) can be as much a matter of public record for consumers living three states away as it can be for CSA customers ten miles from the farm. Modern marketing plans for small businesses include strategies that capitalize on charitable giving that utilizes target-marketing to reach a certain demographic that has demonstrated an affinity for a particular charity. For instance: to target a young, affluent urban donor, an organic farmer would consider a donation of cash or an in-kind contribution of one of the farm’s flagship food products to be served at a cultural event for a specific charity. In exchange for this contribution the farmer would receive recognition in an event program, press coverage, or on a banner at the event. This builds an immediate association with the charity that can trigger name recognition when the young, affluent urban donor assumes the role of a consumer of fresh vegetables or is selecting a CSA to join. Thirty-four percent of the affluent Gen Y and Gen X demographic base tend to attend or volunteer for a charitable event before they contribute to it. In this example of a proverbial “win-win” scenario, there may not be total equality in the exchange of goods or dollars for return, the farm/small business both profits from its relationship with the charity and, on a much higher moral plane, fulfills a significant portion of its implicit social responsibilities. (10)

In the new global economy, business ethics extend well beyond the “dollars and cents”parameters of what was once the way all business was conducted. New business paradigms have shifted to include the requisite importance of integrating social and environmental considerations into any modern business model. [It is important to note that not even the small farm exists outside the global economy. As morality and altruism should, and do, play a large role in this type of “business thinking” in the long term (as these considerations become part of the norm), they will also make good economic sense in terms of the bottom line. [Modernized shipping methods and the internet (especially in the realm of market access/pricing/product quality) has made all farming “local.”] A company or a farm’s reputation (image) can be as much a matter of public record for consumers living three states away as it can be for CSA customers ten miles from the farm. Modern marketing plans for small businesses include strategies that capitalize on charitable giving that utilizes target-marketing to reach a certain demographic that has demonstrated an affinity for a particular charity. For instance: to target a young, affluent urban donor, an organic farmer would consider a donation of cash or an in-kind contribution of one of the farm’s flagship food products to be served at a cultural event for a specific charity. In exchange for this contribution the farmer would receive recognition in an event program, press coverage, or on a banner at the event. This builds an immediate association with the charity that can trigger name recognition when the young, affluent urban donor assumes the role of a consumer of fresh vegetables or is selecting a CSA to join. Thirty-four percent of the affluent Gen Y and Gen X demographic base tend to attend or volunteer for a charitable event before they contribute to it. In this example of a proverbial “win-win” scenario, there may not be total equality in the exchange of goods or dollars for return, the farm/small business both profits from its relationship with the charity and, on a much higher moral plane, fulfills a significant portion of its implicit social responsibilities. (10)

The Environment as the Ultimate Social Responsibility.

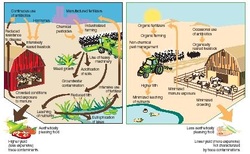

These “social responsibilities” taken to a higher level and beyond, introduces our business model to a broader, social-strata crossing, more complex realm that revolves around one of the most important issues of our day: the environment. Beginning in the period just after WWII (and largely as a result of wartime technology) agriculture changed radically from a manure/relatively organic based system to a petro-chemical based system. From the use of high nitrogen fertilizers to an ever more lethal array of pesticides, agriculture, in its successful quest to modernize, also became a significant source of pollutants. By the mid-1950’s agriculture began to transition from a model that had been primarily the traditional classic family sustenance/surplus with cropping systems based on manure and rotation [note: there were some notable exceptions based on the bonanza farm models of the late 19th century] to a more industrial model that became fully dependent on petroleum to produce crops almost exclusively for commodity markets. This period began an era that is commonly referred to as the Green Revolution. Refined by technology and grown by market demands over succeeding decades the Green Revolution remains, by-in-large, intact and flourishes to this day.While there has certainly been many positive aspects that have resulted from the Green Revolution in terms of feeding the planet and the wealth creating opportunities it has provided, the negative impact that petroleum-based agriculture has had on the environment is so immense and so extremely complex that it may never be able to be fully reversed. Though it is not the purpose of this general discussion to dwell on the nuances of petro-based farming, the problems associated with it provide a model of how a business without a sense of social responsibility can wreak havoc, not just within its operational society, but on a global scale. The impacts of the aggregate of over 2 million farms that operate within the United States (all of which are businesses that operate within and benefit from society) have on society and the environment as a whole cannot be understated:

Agriculture consumes 17% of the petroleum-based energy in this country. [exclusive of refrigeration, transportation etc. costs]

Petroleum based agriculture requires inputs that average 75 times that of traditional agriculture.

Utilizing the laws of thermodynamics, energy inputs employed by modern farm models yield an average input to return ratio of: 4:3

Only 12% of the petroleum-based nitrogen fertilizer applied by farmers is utilized by the plant it was intended to benefit, leaving the

remaining 88% as free or“rogue” nitrogen; a compound that holds a negative charge making it unable to bind to solid soil. In turn, this very mobile (soluble) nitrate travels through the environment causing a plethora of environmental problems that include: an increase in tropospheric ozone levels, an adverse change in biodiversity, an acidification of all water resources (large and small), and eutrophication and hypoxia resulting in habitat and biodiversity loss in coastal ecosystems.

As illustrated by these examples, small acts of irresponsibility by seemingly isolated and independent entities (businesses, in this case farms), can accumulate in a relatively short time to geometrically become a problem beyond any one of its contributors' imagination. The first step for a business in the realm of social responsibility is to realize how it can truly effect the environment of all those who have a connection to it, and act accordingly with responsibility. Removing any moral considerations, there are also reams of peer-reviewed data that specifically support the fact that socially-responsible, environmentally sensitive cultural practices can and do make economic sense, particularly when viewed through a macro-lens. Current (petro) practices result in costs well beyond the price of petroleum, that are passed on to the very customers the business is serving. In examining these costs, it is important to note that all members of society share these added burdens. The USDA found that 71% of cropland in the U.S. lies in watersheds where at least one agricultural pollutant violates criteria for recreation or ecological health. The costs for dealing with these problems are termed shadow prices

and are a measure of the true costs to society in regards to the irresponsible use of petro-chemicals in agriculture. Conversely, in long term

trials, where more environmentally sound and socially responsible techniques are practiced as a whole system or integrated into an existing conventional system, costs to both the farmer and the society have proven to be significantly reduced. Among the savings realized was a 30% reduction in petroleum

costs. As environmentally friendly and socially-conscience practices meet the onus the farmer has to society at large, they can also be a key

component of a good and economically sound business plan. This new paradigm business plan will, above all else, prove that making a fair profit and conducting business in a moral and socially-responsible manner are not mutually exclusive practices but, in fact, synergistic. (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17)

These “social responsibilities” taken to a higher level and beyond, introduces our business model to a broader, social-strata crossing, more complex realm that revolves around one of the most important issues of our day: the environment. Beginning in the period just after WWII (and largely as a result of wartime technology) agriculture changed radically from a manure/relatively organic based system to a petro-chemical based system. From the use of high nitrogen fertilizers to an ever more lethal array of pesticides, agriculture, in its successful quest to modernize, also became a significant source of pollutants. By the mid-1950’s agriculture began to transition from a model that had been primarily the traditional classic family sustenance/surplus with cropping systems based on manure and rotation [note: there were some notable exceptions based on the bonanza farm models of the late 19th century] to a more industrial model that became fully dependent on petroleum to produce crops almost exclusively for commodity markets. This period began an era that is commonly referred to as the Green Revolution. Refined by technology and grown by market demands over succeeding decades the Green Revolution remains, by-in-large, intact and flourishes to this day.While there has certainly been many positive aspects that have resulted from the Green Revolution in terms of feeding the planet and the wealth creating opportunities it has provided, the negative impact that petroleum-based agriculture has had on the environment is so immense and so extremely complex that it may never be able to be fully reversed. Though it is not the purpose of this general discussion to dwell on the nuances of petro-based farming, the problems associated with it provide a model of how a business without a sense of social responsibility can wreak havoc, not just within its operational society, but on a global scale. The impacts of the aggregate of over 2 million farms that operate within the United States (all of which are businesses that operate within and benefit from society) have on society and the environment as a whole cannot be understated:

Agriculture consumes 17% of the petroleum-based energy in this country. [exclusive of refrigeration, transportation etc. costs]

Petroleum based agriculture requires inputs that average 75 times that of traditional agriculture.

Utilizing the laws of thermodynamics, energy inputs employed by modern farm models yield an average input to return ratio of: 4:3

Only 12% of the petroleum-based nitrogen fertilizer applied by farmers is utilized by the plant it was intended to benefit, leaving the

remaining 88% as free or“rogue” nitrogen; a compound that holds a negative charge making it unable to bind to solid soil. In turn, this very mobile (soluble) nitrate travels through the environment causing a plethora of environmental problems that include: an increase in tropospheric ozone levels, an adverse change in biodiversity, an acidification of all water resources (large and small), and eutrophication and hypoxia resulting in habitat and biodiversity loss in coastal ecosystems.

As illustrated by these examples, small acts of irresponsibility by seemingly isolated and independent entities (businesses, in this case farms), can accumulate in a relatively short time to geometrically become a problem beyond any one of its contributors' imagination. The first step for a business in the realm of social responsibility is to realize how it can truly effect the environment of all those who have a connection to it, and act accordingly with responsibility. Removing any moral considerations, there are also reams of peer-reviewed data that specifically support the fact that socially-responsible, environmentally sensitive cultural practices can and do make economic sense, particularly when viewed through a macro-lens. Current (petro) practices result in costs well beyond the price of petroleum, that are passed on to the very customers the business is serving. In examining these costs, it is important to note that all members of society share these added burdens. The USDA found that 71% of cropland in the U.S. lies in watersheds where at least one agricultural pollutant violates criteria for recreation or ecological health. The costs for dealing with these problems are termed shadow prices

and are a measure of the true costs to society in regards to the irresponsible use of petro-chemicals in agriculture. Conversely, in long term

trials, where more environmentally sound and socially responsible techniques are practiced as a whole system or integrated into an existing conventional system, costs to both the farmer and the society have proven to be significantly reduced. Among the savings realized was a 30% reduction in petroleum

costs. As environmentally friendly and socially-conscience practices meet the onus the farmer has to society at large, they can also be a key

component of a good and economically sound business plan. This new paradigm business plan will, above all else, prove that making a fair profit and conducting business in a moral and socially-responsible manner are not mutually exclusive practices but, in fact, synergistic. (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17)

Cultural Practices and Stewardship of the Land

Sound “scientifically based cultural practices” are the physical manifestations of the business of farming. Proper tilling, planting, harvesting, and storage techniques are essential elements in turning a profit on the farm, ergo the greater the efficiencies in these areas, the higher the profit. Because of the previous trending toward the “bigger is better” philosophy, (encouraged by the USDA and state institutions like land-grant colleges particularly in the years from 1972 to the late 1990’s ) small–scale farming was relegated to secondary status, but circa 2003 a paradigm shift occurred in institutional and government thinking as niche farming and alternative agriculture ( organic and sustainable models) became popular, profitable, and presented a vehicle for small and part-time farmers to stay in agriculture and be a viable market force. In a sense these institutions had to play catch-up within the industry, as farmers themselves, aided by the internet, shared self-developed methodologies and experiences. By 2009, the massive force of government money for research provided by the USDA and land-grant colleges throughout the country have helped advanced the technology required to make new inroads into developing new crops and cropping systems as well as providing economically viable methods for conducting environmentally sound practices. Like the fiscal budgeting process, the implementation of sound cultural practices require research and extensive planning. While there are literally hundreds of practices that are involved in cropping systems that have strong economic impact, four of the most essential are:(18)

1. Site selection: While plants are very adaptable and will grow under a wide variety of conditions, yield will vary greatly in direct correlation to the environment in which they are grown. Knowing your soil type, its analysis, light exposure (slope direction) and drainage characteristics can have dramatic impact on the ultimate yield and resulting profit you reap from specific area of your farm. For example: well drained soils with low humus content are capable of producing an “average” yield of vegetables with the aid of enormous and expensive inputs including water, chemical fertilizers, herbicides and various other pesticides. By contrast, the same vegetable may not only yield “higher than average” but require less costly inputs planted in a loam or muck site where the optimal cultural requirements of the vegetable are matched to the corresponding site. Driving this concept to the next level is the idea that there is a “profit center” function for sites of all description on the farm, i.e.: grapes on a well drained, high mineral site or grazing on a site that does not dry until early summer. Site selection considerations, when executed properly, can dramatically increase revenue by enabling higher yields, decreasing labor and capital inputs, and utilizing land conventionally considered as marginal and unproductive.

2.Crop Selection in Terms of Water Demand: In a farming-era replete with genetically manipulated growth hormones and literally hundreds of fertilizer formulations and concoctions, the purest and most important regulator remains water. From livestock to beansprouts, water is the essential and ultimate growth regulator. The ability to precisely control and apply water can produce dramatic results not only in terms of yield but also in term of overall plant health. When a plant is under stress, susceptibility to insect and disease issues is increased and thus the inputs needed to counteract these issues increases production costs. Additionally, because our niche marketing model contains a cosmetic element for “shelf appeal” to meet consumers' expectations and buyers' demands, our product must be free from visual flaws that are the product of insect, drought, and disease pressure. Whether irrigation water is free or purchased, there are both capital and short term expenses related to moving and managing it which must be carefully factored in our budget to maximize and rationalize its use. Understanding the water demands of individual crops is an important consideration and should be a function of our technical manager, and a integrated element of marketing strategy, as every crop selected should have pragmatic production considerations attached to it. (19)

Seasonal

Water Demand

Crop Inches Approximate Demand Range

HIGH

Broccoli 20-25

Onion 5-30

Tomato 20-25

MODERATE

Asparagus 10-18

Cantaloupe 15-20

Cucumber 15-20

LOW

Lettuce 8-12

Radish 5-6

Watermelon 10-15

Sound “scientifically based cultural practices” are the physical manifestations of the business of farming. Proper tilling, planting, harvesting, and storage techniques are essential elements in turning a profit on the farm, ergo the greater the efficiencies in these areas, the higher the profit. Because of the previous trending toward the “bigger is better” philosophy, (encouraged by the USDA and state institutions like land-grant colleges particularly in the years from 1972 to the late 1990’s ) small–scale farming was relegated to secondary status, but circa 2003 a paradigm shift occurred in institutional and government thinking as niche farming and alternative agriculture ( organic and sustainable models) became popular, profitable, and presented a vehicle for small and part-time farmers to stay in agriculture and be a viable market force. In a sense these institutions had to play catch-up within the industry, as farmers themselves, aided by the internet, shared self-developed methodologies and experiences. By 2009, the massive force of government money for research provided by the USDA and land-grant colleges throughout the country have helped advanced the technology required to make new inroads into developing new crops and cropping systems as well as providing economically viable methods for conducting environmentally sound practices. Like the fiscal budgeting process, the implementation of sound cultural practices require research and extensive planning. While there are literally hundreds of practices that are involved in cropping systems that have strong economic impact, four of the most essential are:(18)

1. Site selection: While plants are very adaptable and will grow under a wide variety of conditions, yield will vary greatly in direct correlation to the environment in which they are grown. Knowing your soil type, its analysis, light exposure (slope direction) and drainage characteristics can have dramatic impact on the ultimate yield and resulting profit you reap from specific area of your farm. For example: well drained soils with low humus content are capable of producing an “average” yield of vegetables with the aid of enormous and expensive inputs including water, chemical fertilizers, herbicides and various other pesticides. By contrast, the same vegetable may not only yield “higher than average” but require less costly inputs planted in a loam or muck site where the optimal cultural requirements of the vegetable are matched to the corresponding site. Driving this concept to the next level is the idea that there is a “profit center” function for sites of all description on the farm, i.e.: grapes on a well drained, high mineral site or grazing on a site that does not dry until early summer. Site selection considerations, when executed properly, can dramatically increase revenue by enabling higher yields, decreasing labor and capital inputs, and utilizing land conventionally considered as marginal and unproductive.

2.Crop Selection in Terms of Water Demand: In a farming-era replete with genetically manipulated growth hormones and literally hundreds of fertilizer formulations and concoctions, the purest and most important regulator remains water. From livestock to beansprouts, water is the essential and ultimate growth regulator. The ability to precisely control and apply water can produce dramatic results not only in terms of yield but also in term of overall plant health. When a plant is under stress, susceptibility to insect and disease issues is increased and thus the inputs needed to counteract these issues increases production costs. Additionally, because our niche marketing model contains a cosmetic element for “shelf appeal” to meet consumers' expectations and buyers' demands, our product must be free from visual flaws that are the product of insect, drought, and disease pressure. Whether irrigation water is free or purchased, there are both capital and short term expenses related to moving and managing it which must be carefully factored in our budget to maximize and rationalize its use. Understanding the water demands of individual crops is an important consideration and should be a function of our technical manager, and a integrated element of marketing strategy, as every crop selected should have pragmatic production considerations attached to it. (19)

Seasonal

Water Demand

Crop Inches Approximate Demand Range

HIGH

Broccoli 20-25

Onion 5-30

Tomato 20-25

MODERATE

Asparagus 10-18

Cantaloupe 15-20

Cucumber 15-20

LOW

Lettuce 8-12

Radish 5-6

Watermelon 10-15

3. Primary Tillage Systems, Weed Control and Bed Preparation: The origins of the moldboard plow can be traced back to the Chinese in 3rd century B.C., with significant

improvements made in the United States in the late 18th to mid-19th centuries that subsequently resulted in the version (essentially) we still use today. Moldboard plowing is replete with negative consequences that range from moral to economic and include:

·

1) Enhanced conditions for soil erosion ·

2) Development of “hard-pan,” creating the need for periodic follow-up sub-soil tillage and other remedial drainage methods ·

3) Rapid decline of organic matter in the soil ·

3) Huge carbon-footprint impacts

4) Costly investments in fuel and equipment ·

5) High mid- to- late season weed pressure

Alternative primary tillage systems (those outside utilization of the moldboard plow), like chisel plowing and other reduced tillage methods including certain no-till practices, have their own intrinsic drawbacks; however, their overall benefits outweigh these disadvantages in ways that address the above mentioned problems. New methodologies in no-till systems for vegetables are not only evolving but have become (in selected crops) commercially viable. In a comparison of four tillage systems, tomato yields

remained either consistent or improved in no-till or reduced-till methods versus conventional the moldboard/disk/harrow method system. (20)(21)(22)(23)

4. Soil Management : Understanding the Nature of Soil: There is no generation of farmers who can escape some measure of indictment for disrespecting the soil, the lifeblood of farming. As farming moved from a manure based system (a trend that began as the “Bonanza Farm” movement circa 1870-1890) to a chemical/mineral, then petro-chemical system during the last two-thirds of the 20th century, the farmers’ attitude toward the soil became, at best, 'cavalier.' Agriculture came to ignore the most

basic tenet of agronomy: ‘healthy, productive soil is a complex, biological entity composed of millions of living organisms that interact with each other and the entire environment at large.’ The new thinking relegates soil instead to a sterile media whose primary uses are to provide structural support for plant material and to act as a vessel to hold tons of petroleum based chemicals to bolster these plants until harvest. In a myopic, short-term business point of view there is some merit to this type of thinking: however, it is not the methodology that will work in the long-term for our small farm model with finite resources such as limited funds and acreage to work with. In fact, proper soil management employing a hybridized system that combines time-tested practices such as rotation, fallowing, nitrogen-fixing cover-cropping (green manure), and (where feasible organic based supplements like manure and compost) with modern agronomic theory and method can result in yields that surpass conventional systems in both quantity and quality, with smaller petro-chemical inputs.Smaller inputs translate to lower fuel and fertilizer costs and again

simultaneously meet the socio-environmental standards we have set for our small-farm model.

Making a fair profit and conducting business in a moral and socially responsible manner are not mutually exclusive practices but, in fact, synergistic.

click here to move to the next section: Respect for Our Farming Heritage.

improvements made in the United States in the late 18th to mid-19th centuries that subsequently resulted in the version (essentially) we still use today. Moldboard plowing is replete with negative consequences that range from moral to economic and include:

·

1) Enhanced conditions for soil erosion ·

2) Development of “hard-pan,” creating the need for periodic follow-up sub-soil tillage and other remedial drainage methods ·

3) Rapid decline of organic matter in the soil ·

3) Huge carbon-footprint impacts

4) Costly investments in fuel and equipment ·

5) High mid- to- late season weed pressure

Alternative primary tillage systems (those outside utilization of the moldboard plow), like chisel plowing and other reduced tillage methods including certain no-till practices, have their own intrinsic drawbacks; however, their overall benefits outweigh these disadvantages in ways that address the above mentioned problems. New methodologies in no-till systems for vegetables are not only evolving but have become (in selected crops) commercially viable. In a comparison of four tillage systems, tomato yields

remained either consistent or improved in no-till or reduced-till methods versus conventional the moldboard/disk/harrow method system. (20)(21)(22)(23)

4. Soil Management : Understanding the Nature of Soil: There is no generation of farmers who can escape some measure of indictment for disrespecting the soil, the lifeblood of farming. As farming moved from a manure based system (a trend that began as the “Bonanza Farm” movement circa 1870-1890) to a chemical/mineral, then petro-chemical system during the last two-thirds of the 20th century, the farmers’ attitude toward the soil became, at best, 'cavalier.' Agriculture came to ignore the most

basic tenet of agronomy: ‘healthy, productive soil is a complex, biological entity composed of millions of living organisms that interact with each other and the entire environment at large.’ The new thinking relegates soil instead to a sterile media whose primary uses are to provide structural support for plant material and to act as a vessel to hold tons of petroleum based chemicals to bolster these plants until harvest. In a myopic, short-term business point of view there is some merit to this type of thinking: however, it is not the methodology that will work in the long-term for our small farm model with finite resources such as limited funds and acreage to work with. In fact, proper soil management employing a hybridized system that combines time-tested practices such as rotation, fallowing, nitrogen-fixing cover-cropping (green manure), and (where feasible organic based supplements like manure and compost) with modern agronomic theory and method can result in yields that surpass conventional systems in both quantity and quality, with smaller petro-chemical inputs.Smaller inputs translate to lower fuel and fertilizer costs and again

simultaneously meet the socio-environmental standards we have set for our small-farm model.

Making a fair profit and conducting business in a moral and socially responsible manner are not mutually exclusive practices but, in fact, synergistic.

click here to move to the next section: Respect for Our Farming Heritage.