Our Farming Heritage and the Politics of the American Farm

George Santayana's famous (and often corrupted) quote states," Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

Within the intent of this quote lies the truth that knowledge of the past leads to a greater ability to live in harmony in the present and plan for

the future. Knowing and understanding the roots of agriculture is an integral component of the holistic approach to farming. Farming (and agriculture in

general), in a technical sense, can trace its roots back to prehistoric times, achieving a respectable degree of scientifically-based sophistication by the

early 16th century.

In the United States, prior to the Revolutionary War, farming began to transcend the actual physical acts of animal husbandry

and planting, becoming woven into the very fabric of the nation itself and influencing all aspects of the society, from politics to social issues.The Erie Canal was completed in 1825, providing a supply line west and a valuable water-link to the east coast for agriculturual commodities produced in the West. In the decades preceding the Civil War the influences of the Lyceum Movement opened the rural community to new ideas, new science and new technology, which in turn led to a better understanding of farming as a business and farming as a science. In the decades spanning 1840-1860 railroads expanded their tracks by ten times, allowing farmers in landlocked locations transportation access.

By the end of the Civil War, sophisticated and integrated transportation infrastructures where in place. Labor supplied by a great influx of willing and able immigrants ( a number of them being Old-World farmers) provided the manpower to meet the demand of the agriculturual sector. New technology and technological research fueled greater production. The importance of farming was finally recognized by the establishment of the Department of Agriculture in1862. The Morrill Land Grant College Law was passed in 1862 and land supplied by the Homestead Act, land speculators and the railroads created almost limitless opportunities for new farmers. American agriculture, in a plethora of forms, was established from coast to coast by the end of the 1860’s. Even as the Southern plantation system faded into obscurity, more than half of all Americans derived their income directly from farming. Farm

products accounted for 79% of all export revenue.

In the first decade of the 20th century, farming was still the largest single sector of employment in the United States. Farming, as an industry, accounted for 58% of all exports ($917 million or $23 billion in today’s dollars) and over 30% of the population

engaged in farming. (1)(2)(3)(4)

A Brief Lesson: Agriculture Since the Dawn of Man to the Present , the World View. ( click screen to play)

History Of Agriculture from Farmsphere.com on Vimeo.

PART ONE : The Dawn of a New Country and the Engine of Agriculture.

The importance of agriculture during this period can be appreciated simply by looking at two numbers: farm population as a percent of the work force, and percent of total exports /dollar value. As illustrated below, though the number of farmers decreased over the span due to a shift from rural to urban-based economies, the dollar value of agricultural exports increased exponentially over the same period. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that despite the shifting economy during this period, more than one out of every two Americans farmed (until 1880) and many more performed

the ancillary services such as the processing, transportation, and the commerce associated with farm-produced products.

The importance of agriculture during this period can be appreciated simply by looking at two numbers: farm population as a percent of the work force, and percent of total exports /dollar value. As illustrated below, though the number of farmers decreased over the span due to a shift from rural to urban-based economies, the dollar value of agricultural exports increased exponentially over the same period. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that despite the shifting economy during this period, more than one out of every two Americans farmed (until 1880) and many more performed

the ancillary services such as the processing, transportation, and the commerce associated with farm-produced products.

Overview and Growth of Farm Production 1790-1900

Date Farm population as a % of workforce. % of all exports / value per annum

1790 90% 44% / $4.36 million (tobacco major export)

1810 n/a 75% / $23 million

1819 n/a 87%/$40 million

1829 n/a 65%/$42 million

1839 n/a 69% / 73%/$74 million

1849 n/a 65%/$90 million

1859 58% 81%/$189 million

CIVIL WAR PERIOD

1870 53% 79%/$453 million

1880 49% 76%/$574 million

1890 43% 71%/$703 million

1900 43% 71%/$703 million

(5)(6)

Date Farm population as a % of workforce. % of all exports / value per annum

1790 90% 44% / $4.36 million (tobacco major export)

1810 n/a 75% / $23 million

1819 n/a 87%/$40 million

1829 n/a 65%/$42 million

1839 n/a 69% / 73%/$74 million

1849 n/a 65%/$90 million

1859 58% 81%/$189 million

CIVIL WAR PERIOD

1870 53% 79%/$453 million

1880 49% 76%/$574 million

1890 43% 71%/$703 million

1900 43% 71%/$703 million

(5)(6)

A Brief but Important Review of Milestones, Sucesses and Failures Prior to and During the First Millenium of American Agriculture.

As the commodification of American agriculture evolved, its complexity, its functions and its role in society transcended its core purpose of providing food and clothing. New sciences were developed to improve the processes and production. Agriculture was used as a tool by the powerful to tame frontiers. It was employed by speculators to lure the naïve, the adventurer, and hopeless into visions of a bright future. It gave the young nation economic clout throughout the world and it was an inexhaustible source of revenue for colonial, local, federal and state governments and the bureaucracies set up to regulate it.

As the commodification of American agriculture evolved, its complexity, its functions and its role in society transcended its core purpose of providing food and clothing. New sciences were developed to improve the processes and production. Agriculture was used as a tool by the powerful to tame frontiers. It was employed by speculators to lure the naïve, the adventurer, and hopeless into visions of a bright future. It gave the young nation economic clout throughout the world and it was an inexhaustible source of revenue for colonial, local, federal and state governments and the bureaucracies set up to regulate it.

|

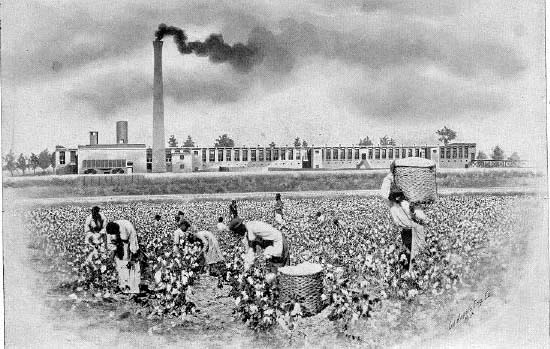

The Colonial Period

In the New England colonies, after a brief era of communal farming, the colonists employed family units to grow and maintain the small subsistence farms that produced the surpluses which became the basis for one of the very dominant models of American agriculture. In the mid- Atlantic and Southern areas, along with the small family farm model, larger farms built through political connections, grants and deceitful land deals began to emerge. Utilizing skills taught to them by Native Americans, these farms, loosely based on the estate/plantation models of imperial England, concentrated mainly on the labor intensive growing of tobacco (adding cotton later) as a cash crop, while growing corn as a food and feed source. While originally employing indentured whites and occasionally Native American labor, the plantation/estate labor was supplanted almost entirely by slaves brought from Africa beginning in 1680. As the South concentrated on labor intensive non-food crops (with the exception of growing corn and rice), the Northern farms produced everything from tobacco to fruit to grain and root crops, adding livestock at the turn of the century (1700). During this period it appears that the Northern farms had a market advantage because of their diversity and their ability to tap into both domestic and export markets, while the South was heavily reliant on England and the export market. It is important to understand that when taking a long look at the underpinnings of American agriculture and its rise, its connection to the spectrum of markets from local to world, is of extreme significance economically, socially and politically. This very unique characteristic of American agriculture is what set it apart from previously practiced systems. This foundation, which was established and evolved during this Colonial period, became entrenched until the Civil War period, when the systems finally clashed and the differences and problems inherent in each came to a head. (7) (8) |

|

Important Milestones 1776-1803 · The invention of the cotton gin in1793 The invention of the cradle and scythe system for grain harvesting.: circa 1795. The invention of the Newberg and Peacock plows followed by the Jethro Wood model. 1797-1814 (approx.) · Improved transportation infrastructure, notably the Lancaster Turnpike – 1794. · The establishment of the agricultural organizations and societies such as The Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of Agriculture Field Husbandry-1785 · The Louisiana Purchase opened new land and gave clear access to the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico – 1803. (4)(5)(6)(9)(11) American Agriculture 1803-1824

For the first part of the decade (1800-1807) agriculture boomed as westward expansion became more practical due to improved roads, water access (Great Lakes/Ohio and Mississippi rivers) and canal systems. North-Eastern agriculture continued to grow in correlation to burgeoning urban growth as the mid-Atlantic region and the upper South continued to grow tobacco and corn, and became the main foodstuff supplier for the Deep South, which was so consumed with cotton production that it could not supply its own food. With 75% of all exports now derived from agriculture and more than 80% of the population employed by farms or the farm related industries, the nation went into economic shock when Thomas Jefferson introduced the Embargo Act of 1807 and the subsequent Non-Intercourse Act of 1809. Both controversial acts were designed to address a number of mainly maritime problems the U.S. had been experiencing as a consequence of trading with Britain and France as these countries engaged in yet another power struggle for control of Europe. By virtually eliminating trade with these two chief importers of American goods (overwhelmingly agricultural in nature) Jefferson created a whole new set of problems for farmers and the populace in general. These acts (Embargo Act of 1807 and Non-Intercourse Act of 1809) were repealed, but by then, the British and other former importers of U.S. farm products discovered alternative sources, specifically in South America. (4)(5)(6)(9)(11) |

The Revolution to the Turn of the Century

The immediate post-Revolutionary War period temporarily plunged the agriculture market and the expansion of agriculture into a period of uncertainty and chaos, Gradually, after 1783, trade-alliances began to re-form and westward expansion moved forward.The invention of the cotton gin in1793 changed the complete complexion of Southern agriculture. In the North, agriculture continued its ponderous metamorphosis from the subsistence/surplus model to a commodification model. Historical economist Robert Sherry characterizes this conversion process as a shift to a “commodity-money-commodity” cycle in which the entire production of the farm was saleable. As the West opened, this conversion continually repeated itself: frontier settlers farmed for subsistence first, then became established, producing small surpluses, then expanded and created large commodity surpluses for sale.At the turn of the century (1800) virtually every leader of the nation was still a farmer or had agrarian roots; as such, men like Jefferson and Washington had both a personal and business stake in the direction agriculture would take. Moving forward into the new century farmers began to lose their independence and started to became both dependent and resentful of the role government played in their everyday dealings. After 1783, all unsettled land came under the authority of the federal government. Ironically, plantation owner Thomas Jefferson was an advocate for the small, independent/family farm model and it was legislation written by him in 1785 (Ordinance of 1785 and follow-up Northwest Ordinance of 1787) that was truly the first significant example of how the government could directly influence the direction of farming in the United States and simultaneously raise revenue. It was this legislation that set federal land policy precedent and remained viable until the passage of the Homestead Act of 1863. With the acceptance of a money-based system, farmers ceded more of their independence over to governmental entities and as such, found themselves at greater mercy to the whims of these entities. According to National Archives records, literally tens of millions acres of government land (unsubstantiated sources put the number as high as 70 million acres), ranging from 100 to 1100 acres, some assignable, were granted to veterans of both the Continental Army and the War of 1812 through 1858 much of which was eventually converted to farmland. (9)(10)(11)(12)(13)(14) While the government continued to use agriculture as a pawn

through the War of 1812, new inventions and ideas about farming began to emerge. Transportation of goods improved greatly. Though short lived, thousands of miles of “farmer’s” or plank roads built specifically for the movement of heavy freight were built. The canal building movement began in earnest and planning for the Erie Canal was underway. Shortly after Robert Fulton launched his steamboat, the Claremont in 1807, newer versions designed specifically for carrying freight were developed and put to use from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, greatly enhancing the movement of farm commodities and expanding markets exponentially. Specialization continued in the North, and in the newly opened mid-West a movement toward creating a corn and grain belt began. At first mainly a novelty, the canning industry offered farmers an outlet for their goods, with the first commercial operation established in 1812. From government agencies to private advocacy groups, farming began to be looked at as an organized and integrated entity: in 1810 the Agricultural Museum magazine was published, followed by the American Farmer and Plough Boy in 1819. New York State established the New York Board of Agriculture in 1819, and in 1820 and 1825 respectively, the House of Representatives and the Senate establish federal Agriculture Committees. Following a brief economic downturn that reached its peak in 1819, American agriculture regained an a era of prosperity driven again by new technologies, new trade policies, and further advances in technology and education. Following the general trend in the country towards greater education of the masses, i.e.: public schools, the Lyceum Movement, the rural community was opened to new ideas, new science and new technology which in turn led to a better understanding of farming as a business and farming as a science. Men such Edmund Ruffin, the father of American agronomy (An Essay on Calcareous Manures), moved agriculture radically and rapidly forward by helping farmers make a scientific connection between what they did culturally on the land and how it affected the land over time. To many agricultural historians and economists, this time in history represented an era when the true commercialization of farming was realized.(15)(16)(17)(18) |

1825-1860 Agricultural Ups, Downs, and the Impending Conflict of the Civil War.

The Erie Canal was completed in 1825, providing a supply line west and a valuable water-link to the east coast for commodities produced in the West. The 1820 Land Act, over the course of the next two decades, enabled many more citizens to become landowners, in fact more than doubling the sale of public lands over the previous twenty years (1800-29:16 million acres. 1821-1841:75 million acres). Additionally, preemption laws were passed and revised continuously during this period (1820-41), giving

squatters various degrees of rights to the land they settled on and worked. Historian David Danbom illustrates the rise and links formed between the country’s growing industrial center and agriculture, citing as an example the story of Proctor and Gamble, who moved their operations to Cincinnati, the “swine capital of the west,” to be close to a reliable supply of lard for soap and candle making. He further illustrates this symbiosis by pointing to the fact that off-season farm labor increasingly found a place in the industrial centers, providing labor for the processing of agricultural commodities as well as supplemental income for the farm family. As farming aided industry, industry provided for the farmer in the form of new technology: within the span of three years, McCormick introduced the mechanical reaper, John Deere, the steel plow, and Avery and Pitts their improved threshing machine.

In 1830, Andrew Jackson culminated a personal campaign, that spanned over 20 years, against the “Five Civilized Tribes” of the Southeast with the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.23 This law forcefully (see “Trail of Tears”) ended all legal claims native American tribes had on land that was coveted by Southern plantation owners and settler farmers. In a larger sense this event served to relegate the role the indigenous people played in early American agriculture to relative insignificance. The farming methods and crops that allowed the early settlers to survive came from a hybridized adaptation of Native American agriculture; and with the exception of a minor mention around Thanksgiving, there is but minor recognition of that fact.

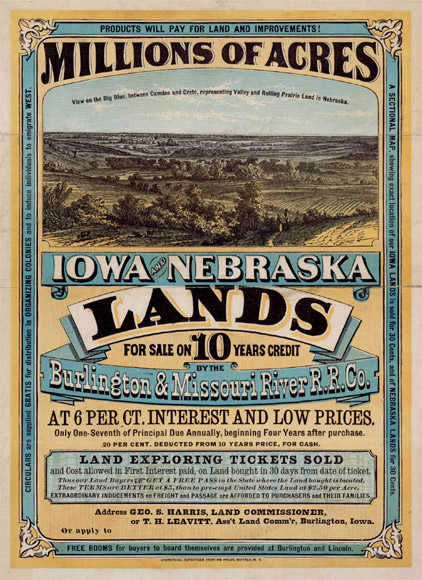

In 1841 the second Preemption Act was passed opening up additional public lands for settlement at a relatively modest price of $1.25/acre for squatters who had lived on a plot of up to 160 acres. In the decades spanning 1840-1860 railroads expanded their tracks by ten times, allowing farmers in landlocked locations transportation access. As expansion continued, the specter of the one -free/one- slave state, Missouri Compromise of 1820 loomed in the background as political and economic tensions between Southern and Northern farmers continued to build. Beyond all moral and philosophical considerations, there were high-stakes economic issues in play, including a perception by those in the north that the slave trade gave the Southern states an unfair competitive advantage in agricultural production and processing. Additionally, the aforementioned dealings with the farming Indian tribes of the South by Southerners, including illegal land grabs, offended the Northerners and flew in the face of those on the federal level that promoted farming by Native Americans as a peaceful and humane method to handle the “Indian problem”and a path to assimilation. In a fashion, the North was able to counter the advantages of

slave labor, and at the same time continue the supply of free-white farmers for expansionism by promoting and sanctioning liberal immigration policies that favored Northern Europeans. Fueled by the Irish Potato Famine of 1845 and economic problems throughout Europe, immigration to the U.S. increased

by almost 600% in the period between 1841 and 1860 (4,311,465) with 87% of this population coming from Ireland, Germany, and Great Britain. Though

many of these immigrants came as a result of problems at home, many also came because of the lure of land ownership and farming on the new frontier

accompanied by incentives coming from railroads, the largest private sector land owners. (19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)

The Erie Canal was completed in 1825, providing a supply line west and a valuable water-link to the east coast for commodities produced in the West. The 1820 Land Act, over the course of the next two decades, enabled many more citizens to become landowners, in fact more than doubling the sale of public lands over the previous twenty years (1800-29:16 million acres. 1821-1841:75 million acres). Additionally, preemption laws were passed and revised continuously during this period (1820-41), giving

squatters various degrees of rights to the land they settled on and worked. Historian David Danbom illustrates the rise and links formed between the country’s growing industrial center and agriculture, citing as an example the story of Proctor and Gamble, who moved their operations to Cincinnati, the “swine capital of the west,” to be close to a reliable supply of lard for soap and candle making. He further illustrates this symbiosis by pointing to the fact that off-season farm labor increasingly found a place in the industrial centers, providing labor for the processing of agricultural commodities as well as supplemental income for the farm family. As farming aided industry, industry provided for the farmer in the form of new technology: within the span of three years, McCormick introduced the mechanical reaper, John Deere, the steel plow, and Avery and Pitts their improved threshing machine.

In 1830, Andrew Jackson culminated a personal campaign, that spanned over 20 years, against the “Five Civilized Tribes” of the Southeast with the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.23 This law forcefully (see “Trail of Tears”) ended all legal claims native American tribes had on land that was coveted by Southern plantation owners and settler farmers. In a larger sense this event served to relegate the role the indigenous people played in early American agriculture to relative insignificance. The farming methods and crops that allowed the early settlers to survive came from a hybridized adaptation of Native American agriculture; and with the exception of a minor mention around Thanksgiving, there is but minor recognition of that fact.

In 1841 the second Preemption Act was passed opening up additional public lands for settlement at a relatively modest price of $1.25/acre for squatters who had lived on a plot of up to 160 acres. In the decades spanning 1840-1860 railroads expanded their tracks by ten times, allowing farmers in landlocked locations transportation access. As expansion continued, the specter of the one -free/one- slave state, Missouri Compromise of 1820 loomed in the background as political and economic tensions between Southern and Northern farmers continued to build. Beyond all moral and philosophical considerations, there were high-stakes economic issues in play, including a perception by those in the north that the slave trade gave the Southern states an unfair competitive advantage in agricultural production and processing. Additionally, the aforementioned dealings with the farming Indian tribes of the South by Southerners, including illegal land grabs, offended the Northerners and flew in the face of those on the federal level that promoted farming by Native Americans as a peaceful and humane method to handle the “Indian problem”and a path to assimilation. In a fashion, the North was able to counter the advantages of

slave labor, and at the same time continue the supply of free-white farmers for expansionism by promoting and sanctioning liberal immigration policies that favored Northern Europeans. Fueled by the Irish Potato Famine of 1845 and economic problems throughout Europe, immigration to the U.S. increased

by almost 600% in the period between 1841 and 1860 (4,311,465) with 87% of this population coming from Ireland, Germany, and Great Britain. Though

many of these immigrants came as a result of problems at home, many also came because of the lure of land ownership and farming on the new frontier

accompanied by incentives coming from railroads, the largest private sector land owners. (19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)

|

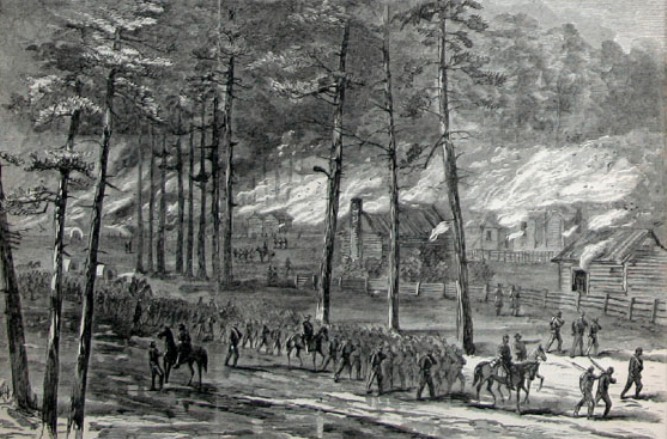

1860-1870. The War and Aftermath.

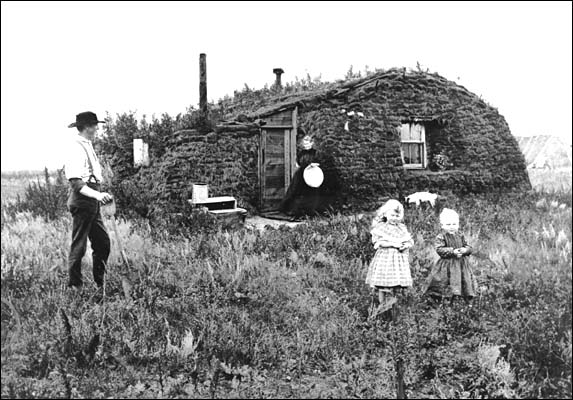

The federal government also created new incentives with the passage of the Homestead Act of 1862 which made public land available to immigrants.With the Civil War in full motion and slavery no longer a consideration, the government was now able to open the estimated 1.5 billion acres of public land, in 160 acre parcels, to any one who was willing to register, homestead for five years, and pay a minimal fee. Because the land was transferable to one’s heirs, the incentive was even greater, and over the course of time, the Homestead Act succeeded in creating the foundation for a new class of family farmers in the west and the beginnings of a Western middle-class. Important milestones of the decade: 1) a sophisticated and integrated transportation infrastructure in place 2)the influx of willing and able immigrants ( a number of them being Old-World farmers) 3) new technology and technological research ongoing ( the Department of Agriculture was finally established in 1862 and the Morrill Land Grant College Law was passed) 4) land supplied by the Homestead Act 5) land speculators and the railroads promoting and profiting on western expansion American agriculture, in a plethora of forms, was established from coast to coast by the end of the 1860’s. Many areas began to differentiate according to location, environmental conditions, markets and core demographics. The North in response to the growth of great urban centers and the war itself, grew a wide diversity of fruit, vegetables, some corn and grain, and produced the preponderance of the poultry and dairy products in the country; and the family- farm model there, became more efficient and technologically oriented. In the Ohio, the Mid-West, and upper Mid-West, corn and livestock, in particular the pork industry, began to dominate, as the beginnings of the corn-belt were being established. California and the Northwest, with it Pacific Ocean influenced mild climate, mimicked the Northeast in its diverse approach to agriculture (though generally, the farm acreage was greater).(24)(25) |

1865-1870 The Devastation of Southern Agriculture and the Rise of the Great Plains

.After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, Southern agriculture was left with no foreign markets, an inability to feed itself, no infrastructure to transport goods, and a now-free and landless, former slave population estimated to be over 4 million strong. The capital loss to the South as a result of emancipation was $1.5 billion or put into perspective, twenty times the 1860 federal budget. The federal government was woefully ill-equipped and unprepared to deal with the problems of the post-war South and the demands of an itinerant and largely uneducated population. The Southern Homestead Act (“forty acres and a mule”) of 1866 was a weak and incomplete effort by the federal government to provide former slaves with a start, but with no capital or credit available to the former slaves, and no real administrative infrastructure behind it, there was little chance that this act was anything more than a symbolic effort that served to muddy an already chaotic situation. Large landowners still owned the majority of land in 1870 but there was no system in place to provide labor and as a result, the landowners first tried to set up a contract labor situation with former slaves. This system with its delayed payments and gang-labor structure looked and acted much like slavery, and like the Southern Homestead Act, was doomed to failure almost as soon as it started. The compromise came with the establishment of the sharecropper system, in which land rented from the plantation owner was worked on shares with a percentage of the crop going back to the landowner. Though sharecropping was fraught with inequities and disincentives, it was a stop-gap measure that at least provided some breathing room for Southern agriculture as it began to adapt and reestablish itself after the War. As the century ground forward, new ideas and hybrid-sharecropping adaptations came into being as the South struggled to regain a semblance of its former agriculture industry. In the Great Plains area that spanned from of Texas to the Dakotas, much of the agricultural industry revolved around the production of beef and to a lesser extent, sheep. The grasslands of the region initially provided a free and seemingly limitless supply of feed for raising beef cattle and sheep for wool. Crop farming was limited to the production of feed for horses. In the short span of its heyday, which lasted 20-30 years, prairie cattle-ranching expanded from the southern to the northern plains rapidly with its epicenter in Kansas. Eventually, drought, over-grazing,overproduction, and pressure from the railroads and the expansion of farming enhanced by favorable federal legislation reduced the industry. Ironically, one of the “new” farming technology models: the factory or Bonanza farm, that supplanted open-range grazing in the Plains also provided elements of agricultural management that led to the more manageable feedlot system; a system that all but replaced traditional cattle ranching. This Bonanza-farm model begun in the Northern plains, though short-lived and relegated to just a footnote in most historical accounts of the era, served to become a harbinger of one direction American agriculture took, and provided management models that have been hybridized and applied throughout the entire industry, and as such, Bonanza farming deserves a serious mention.(26) |

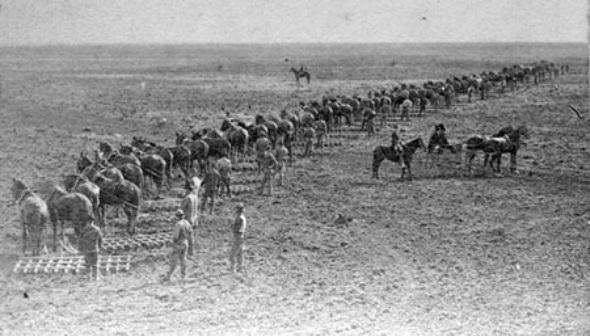

The Era of the Bonanza Farm: How Human Arrogance Led To Failure

The long term success of farming and specifically farming as a commercially viable enterprise requires that its practitioners recognize and maintain a unique relationship with, and awareness of, the environment. Those enterprises that have ignored this most basic caveat have ultimately ended in failure. In the history of American agriculture, the Bonanza farm model which began in the 1870’s, and peaked within 10 years of its inception (fading to insignificance by the early 1900’s), provides a textbook lesson of how human arrogance in defiance of nature led to failure on a grand scale.The Bonanza farm came largely into being as an end-result of conditions

facilitated by numerous government acts and actions primarily during and immediately after the Civil War.Though the door was opened by the Preemption Act of 1841, the real business of land speculation did not begin in earnest until the passage of the Homestead Act of 1862. Clever land speculators could engage the services of “dummy entrymen” who could amass tracts of up to 1200 acres, meet legal requirements for ownership and then, in turn, resell these properties to speculators and railroads. Additionally, between 1862 and 1871, Congress granted over 127,628,000 acres to various railroads to encourage them to extend their lines into the new territories of the west. With these large tracts of land in hand, railroads themselves entered the real estate business using this virtually free land as a source of capital to not only expand but to cover shortfalls in their own revenue stream. By selling the land to speculators and at the same time encouraging large scale farming, the railroads gained a double advantage as they held a monopoly on the land closest to rail lines and the exclusive means to move product produced on the farms to a mass market. The most famous and the first pure example of the Bonanza farm was the Dalrymple farm, begun by the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1871. Located in the Red River Valley along the Minnesota-Dakota Territory border and managed by Oliver Dalrymple, this 1280 acre farm (later expanded) produced thirty-two thousand bushels of wheat during its first year of operation, an unprecedented 25 bushels per acre (respectable even by today’s standards). The initial success of the Dalrymple farm spurred on the Bonanza farm movement eventually leading to the creation of mega-enterprises that ranged on the average of 3-30k acres with the largest, the John Miller Company farm, owning

and operating 59k acres. Because of the cheap and abundant capital provided by the railroad, land consortiums and speculators, these farms were seemingly at a great advantage over their conventional farm model counterparts, specifically the family farm/homesteader. The Bonanza operations were able to utilize the latest technological, innovations such as steam engines and threshing machines, and the latest in horticultural advances, including improved strains of spring wheat hybridized to

the semi-arid and often harsh environment of the Great Plains. With these advantages, the Bonanza model experienced a brief period of prosperity that spanned the 1870’s-80’s and spawned others to follow suit. By the late 1880’s, flaws within the Bonanza farm model, such as overproduction, reliance on a monoculture, skill

specialization and high outside labor demands, in terms of sheer numbers in the related labor costs began to emerge. These flaws combined with outside forces

including weather, foreign competition, high taxes and a plethora of social, political and economic changes bought about the rapid demise of this “darling” of new agriculture in less than a generation. According to Kenneth Sylvester author of The Limits of Rural Capitalism,most of the original Bonanza enterprises were subdivided and sold to smaller farmers by the mid-1890. Ownership of the Bonanza farms consisted mainly of absentee investors and speculators who

never set foot on the land themselves and hired professional managers to operate the farms. Though the availability of ready and cheap cash provided by these

investors proved a short term advantage to the Bonanza operation, the lack of a physical connection to the land proved a long term disadvantage. With profit

the overriding factor, the onus of responsible stewardship of the land was all but absent, putting the managers in the position of having the primary function of providing a consistently favorable return on investment above all else. The typical farm was broken down into units ranging in size from 3-5k acres, with a

separate manager responsible for each unit and with each unit broken down into 1200 acre stations managed by a foreman. Work crews, by any standard were

massive and specialized. The aforementioned Oliver Dalrymple operation, in its heyday, employed a harvesting crew of over a 1000 men, operating 30 separate

threshing crews. Accounts of the period found in scholarly journals, specifically those that delve into the economic aspects of the Bonanza farm model, agree that the management of such large workforces with their accompanying problems and inefficiencies occupied an inordinate amount of the management time. Additionally, manager compensation was tied to yields, relegating any beneficial, and long- term cultural practices as secondary considerations. Ultimately this management style

and the seemingly inexhaustible supply of land led to a “slash and burn” attitude (despite the technology and sophisticated agronomics of the time) which

filtered down to the workforce itself. With timing being the most critical factor in both the sowing and harvesting of a crop, particularly on the scale of the Bonanza farms, a large and dichotomous workforce had to be recruited. On one end of the workforce was the unskilled component that provided the hand labor for the farm. Because the typical Bonanza operation would seasonally utilize up to one-thousand or more hands, migrant labor was a necessity. Hiram Drache in his book, The Day of the Bonanza: the History of Bonanza Farming in the Red River Valley of the North, states that as the number of Bonanza farms began to increase the demand for migrant labor increased to the point that it exceeded the supply, which consequently increased the price of migrant labor; two noteworthy conditions that put the Bonanzas at a competitive disadvantage when compared to the relatively self-contained family/homestead operation. On the other end of the labor spectrum was the specialized labor that included working foremen, steam tractor engineers, ploughmen and experienced farmers. Again, the finite supply of labor that possessed the skill-sets required, coupled with the cost of such labor, put the Bonanza operation at a disadvantage that was only exacerbated when environmental conditions and market forces caused price fluctuations that impacted not only the net profit but also caused severe cash flow problems . Without the diversity of crops and animals found in the smaller family-farm models, the wheat monoculture practiced on the majority of the Bonanzas made them unable to “ride-out” both natural and man-made tough times. When environmental conditions were conducive to wheat growing, they could flourish, providing that the market was able to absorb their crop. When yields were down due to drought, insect or disease problems, the Bonanza had no contingency or backup crop to mitigate the losses. At the onset of the Bonanza farm, Europe was still in the

middle of a population increase (estimated to have doubled within the span of a century) that exceeded its own ability to feed itself, a condition that created an ideal market for Red River Valley wheat. By 1895, European agriculture had advanced to the point that it became self-sufficient, driving wheat prices down and creating surpluses in America. As the surplus grew, the price of wheat declined from a high of $1.05 per bushel between 1870 and 1880 to a thirty-year low of $.653 in the 1890’s. Though the Bonanza farm movement managed to hang on into the new century, in the end it was both a victim of its own success and a harbinger of the direction agriculture would eventually take through the new century and beyond. It would be irresponsible not to recognize the technological, managerial and scientific knowledge that were an important and positive contribution to American agriculture. As agriculture entered a new phase, the specialization concept that was born out of this era, particularly in the livestock industry, has become an integral part of modern agriculture. Bonanza farming illustrated that the corporate farm model was not

equipped to deal with the great environmental challenges that arise when attempting to establish a monoculture of a seasonable crop on fragile land. In

this way, it validated the diversified family-farm model that could adapt and offer creative and cooperative solutions to “nature’s curveballs” and at the same time has shown there is no one system that is universally adaptable to the very diverse science of farming. (27)(28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34)

The long term success of farming and specifically farming as a commercially viable enterprise requires that its practitioners recognize and maintain a unique relationship with, and awareness of, the environment. Those enterprises that have ignored this most basic caveat have ultimately ended in failure. In the history of American agriculture, the Bonanza farm model which began in the 1870’s, and peaked within 10 years of its inception (fading to insignificance by the early 1900’s), provides a textbook lesson of how human arrogance in defiance of nature led to failure on a grand scale.The Bonanza farm came largely into being as an end-result of conditions

facilitated by numerous government acts and actions primarily during and immediately after the Civil War.Though the door was opened by the Preemption Act of 1841, the real business of land speculation did not begin in earnest until the passage of the Homestead Act of 1862. Clever land speculators could engage the services of “dummy entrymen” who could amass tracts of up to 1200 acres, meet legal requirements for ownership and then, in turn, resell these properties to speculators and railroads. Additionally, between 1862 and 1871, Congress granted over 127,628,000 acres to various railroads to encourage them to extend their lines into the new territories of the west. With these large tracts of land in hand, railroads themselves entered the real estate business using this virtually free land as a source of capital to not only expand but to cover shortfalls in their own revenue stream. By selling the land to speculators and at the same time encouraging large scale farming, the railroads gained a double advantage as they held a monopoly on the land closest to rail lines and the exclusive means to move product produced on the farms to a mass market. The most famous and the first pure example of the Bonanza farm was the Dalrymple farm, begun by the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1871. Located in the Red River Valley along the Minnesota-Dakota Territory border and managed by Oliver Dalrymple, this 1280 acre farm (later expanded) produced thirty-two thousand bushels of wheat during its first year of operation, an unprecedented 25 bushels per acre (respectable even by today’s standards). The initial success of the Dalrymple farm spurred on the Bonanza farm movement eventually leading to the creation of mega-enterprises that ranged on the average of 3-30k acres with the largest, the John Miller Company farm, owning

and operating 59k acres. Because of the cheap and abundant capital provided by the railroad, land consortiums and speculators, these farms were seemingly at a great advantage over their conventional farm model counterparts, specifically the family farm/homesteader. The Bonanza operations were able to utilize the latest technological, innovations such as steam engines and threshing machines, and the latest in horticultural advances, including improved strains of spring wheat hybridized to

the semi-arid and often harsh environment of the Great Plains. With these advantages, the Bonanza model experienced a brief period of prosperity that spanned the 1870’s-80’s and spawned others to follow suit. By the late 1880’s, flaws within the Bonanza farm model, such as overproduction, reliance on a monoculture, skill

specialization and high outside labor demands, in terms of sheer numbers in the related labor costs began to emerge. These flaws combined with outside forces

including weather, foreign competition, high taxes and a plethora of social, political and economic changes bought about the rapid demise of this “darling” of new agriculture in less than a generation. According to Kenneth Sylvester author of The Limits of Rural Capitalism,most of the original Bonanza enterprises were subdivided and sold to smaller farmers by the mid-1890. Ownership of the Bonanza farms consisted mainly of absentee investors and speculators who

never set foot on the land themselves and hired professional managers to operate the farms. Though the availability of ready and cheap cash provided by these

investors proved a short term advantage to the Bonanza operation, the lack of a physical connection to the land proved a long term disadvantage. With profit

the overriding factor, the onus of responsible stewardship of the land was all but absent, putting the managers in the position of having the primary function of providing a consistently favorable return on investment above all else. The typical farm was broken down into units ranging in size from 3-5k acres, with a

separate manager responsible for each unit and with each unit broken down into 1200 acre stations managed by a foreman. Work crews, by any standard were

massive and specialized. The aforementioned Oliver Dalrymple operation, in its heyday, employed a harvesting crew of over a 1000 men, operating 30 separate

threshing crews. Accounts of the period found in scholarly journals, specifically those that delve into the economic aspects of the Bonanza farm model, agree that the management of such large workforces with their accompanying problems and inefficiencies occupied an inordinate amount of the management time. Additionally, manager compensation was tied to yields, relegating any beneficial, and long- term cultural practices as secondary considerations. Ultimately this management style

and the seemingly inexhaustible supply of land led to a “slash and burn” attitude (despite the technology and sophisticated agronomics of the time) which

filtered down to the workforce itself. With timing being the most critical factor in both the sowing and harvesting of a crop, particularly on the scale of the Bonanza farms, a large and dichotomous workforce had to be recruited. On one end of the workforce was the unskilled component that provided the hand labor for the farm. Because the typical Bonanza operation would seasonally utilize up to one-thousand or more hands, migrant labor was a necessity. Hiram Drache in his book, The Day of the Bonanza: the History of Bonanza Farming in the Red River Valley of the North, states that as the number of Bonanza farms began to increase the demand for migrant labor increased to the point that it exceeded the supply, which consequently increased the price of migrant labor; two noteworthy conditions that put the Bonanzas at a competitive disadvantage when compared to the relatively self-contained family/homestead operation. On the other end of the labor spectrum was the specialized labor that included working foremen, steam tractor engineers, ploughmen and experienced farmers. Again, the finite supply of labor that possessed the skill-sets required, coupled with the cost of such labor, put the Bonanza operation at a disadvantage that was only exacerbated when environmental conditions and market forces caused price fluctuations that impacted not only the net profit but also caused severe cash flow problems . Without the diversity of crops and animals found in the smaller family-farm models, the wheat monoculture practiced on the majority of the Bonanzas made them unable to “ride-out” both natural and man-made tough times. When environmental conditions were conducive to wheat growing, they could flourish, providing that the market was able to absorb their crop. When yields were down due to drought, insect or disease problems, the Bonanza had no contingency or backup crop to mitigate the losses. At the onset of the Bonanza farm, Europe was still in the

middle of a population increase (estimated to have doubled within the span of a century) that exceeded its own ability to feed itself, a condition that created an ideal market for Red River Valley wheat. By 1895, European agriculture had advanced to the point that it became self-sufficient, driving wheat prices down and creating surpluses in America. As the surplus grew, the price of wheat declined from a high of $1.05 per bushel between 1870 and 1880 to a thirty-year low of $.653 in the 1890’s. Though the Bonanza farm movement managed to hang on into the new century, in the end it was both a victim of its own success and a harbinger of the direction agriculture would eventually take through the new century and beyond. It would be irresponsible not to recognize the technological, managerial and scientific knowledge that were an important and positive contribution to American agriculture. As agriculture entered a new phase, the specialization concept that was born out of this era, particularly in the livestock industry, has become an integral part of modern agriculture. Bonanza farming illustrated that the corporate farm model was not

equipped to deal with the great environmental challenges that arise when attempting to establish a monoculture of a seasonable crop on fragile land. In

this way, it validated the diversified family-farm model that could adapt and offer creative and cooperative solutions to “nature’s curveballs” and at the same time has shown there is no one system that is universally adaptable to the very diverse science of farming. (27)(28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34)

|

Moving Toward a New Century

As the dust from the chaos of the Civil War settled and the country got back to the business of growing and producing, agriculture again soared and paralleled the surge of industrialization. The urban population tripled and the farm population doubled in the span of the 30 years (1870-1900). The wheat and corn belts were firmly established and cotton production in the South reached record highs with an average of an astounding 225% production increase in the period between 1870 and 1880 alone. By the mid-1880’s, state sponsored and sanctioned irrigation systems expanded the scope of what could be grown, specifically in the Pacific and Northwest regions, giving rise to a massive vegetable and fruit industry.While the government and the newly formed U.S.D.A. did all it could to encourage expansion and new methodology, it came up short on the economic- management side of this now massive industry. Frustrated with the government ineptitude and floundering, taxes, big business (specifically the railroads and big-time processors) and the banks, farmers from all regions began to organize and enter the political arena.Farmers became activists creating movements to fill the gaps left by the government, creating a voice for themselves in the arena of national politics, and forming economic alliances that could deal with the railroads, industry and the banks. Among these movements and organizations were the Greenbackers, the Grangers, the Alliance movement and in the 1890’s, the Populists. The Granger movement and the Alliance movement concentrated on the cooperative approach, dealing with railroads and big industry. The Greenbackers focused on price stability and markets. |

This era marked the turning point for government involvement in agriculture industry and conversely it changed what the agriculture industry and community expected from government. At first the USDA’s function was to offer and distribute the very latest in scientific knowledge and new cultural techniques to farmers and in this, they succeeded very well through land-grant colleges and experiment stations; Cornell University being among the finest examples, even into the present. As this science was disseminated, it began to have a distinct impact on rural life and culture. Education, at least at a minor level, was becoming a requirement in order for farmers to be competitive and market savvy. Black schools were established, and with that came a generation of educated and literate blacks who became a political constituency. As the mission of the USDA continued to expand, so too did the bureaucracy that drove it. In 1889 the USDA obtained cabinet level status and with that, the department solidified its growing political influence and power. (35)(36)(37) |

A New Era of Farming Begins:

At the turn of the century, after over a decade of trial and error, tremendous growth, western expansionism and phenomenal scientifically-based achievement, American agriculture emerged as an organized and politically potent entity. With the USDA becoming an integral part of the Executive branch, farmers finally had the ear of the country they had so desired. As the USDA strayed further from their original mission of scientific and technological support for the farming industry and began to formulate and regulate almost every aspect of farming and farm policy, the adage “Be careful what you wish for” has taken on a special significance for the generations of

American farmers who followed. Those, many whom are descendents of the Populists and Greenbackers and Grangers, got the regulation and government control they

desired but at the price of their independence and individualism. From this point forward the success, and often the failure, of the American farmer, as well as his counterparts in other countries, would be directly linked to the farm policies of the United States.

PART TWO : HIGHLIGHTS OF 1900 TO WW II

In the first decade of the 20th century, farming was still the largest single sector of employment in this country. Farming, as an industry, accounted for 58% of all exports ($917 million or $23 billion in today’s dollars) and over 30% of the population engaged in farming. As the new century arrived, the relationship between agriculture and the government, from the local to the federal level, had changed rapidly and radically over the course of the last decade. This was an evolution that saw farmers demanding more from the government and the beginnings of unprecedented government control of almost every aspect of farming. Setting the tone for what is often called the “Golden Age of U.S. Agriculture” (1900- circa.1920) were, in terms of legislation, the legacies that evolved from the Homestead Act of 1862, the Morrill Act(s) of 1862( 2nd in 1890), Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1890 and the Newland’s Reclamation Act of 1902. With the USDA at cabinet level status and powerful Congressional agricultural committees that included members of the Populist Party, agriculture was a national priority. (38)

At the turn of the century, after over a decade of trial and error, tremendous growth, western expansionism and phenomenal scientifically-based achievement, American agriculture emerged as an organized and politically potent entity. With the USDA becoming an integral part of the Executive branch, farmers finally had the ear of the country they had so desired. As the USDA strayed further from their original mission of scientific and technological support for the farming industry and began to formulate and regulate almost every aspect of farming and farm policy, the adage “Be careful what you wish for” has taken on a special significance for the generations of

American farmers who followed. Those, many whom are descendents of the Populists and Greenbackers and Grangers, got the regulation and government control they

desired but at the price of their independence and individualism. From this point forward the success, and often the failure, of the American farmer, as well as his counterparts in other countries, would be directly linked to the farm policies of the United States.

PART TWO : HIGHLIGHTS OF 1900 TO WW II

In the first decade of the 20th century, farming was still the largest single sector of employment in this country. Farming, as an industry, accounted for 58% of all exports ($917 million or $23 billion in today’s dollars) and over 30% of the population engaged in farming. As the new century arrived, the relationship between agriculture and the government, from the local to the federal level, had changed rapidly and radically over the course of the last decade. This was an evolution that saw farmers demanding more from the government and the beginnings of unprecedented government control of almost every aspect of farming. Setting the tone for what is often called the “Golden Age of U.S. Agriculture” (1900- circa.1920) were, in terms of legislation, the legacies that evolved from the Homestead Act of 1862, the Morrill Act(s) of 1862( 2nd in 1890), Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1890 and the Newland’s Reclamation Act of 1902. With the USDA at cabinet level status and powerful Congressional agricultural committees that included members of the Populist Party, agriculture was a national priority. (38)

|

Teddy Roosevelt and the Country Life Movement

When the country experienced financial panics and downturns(1819, 1837, 1857, 1854, 1873, and 1893) the farmer and rurual population at-large were affected profoundly. As the commercialization and specialization of farming continued, farmers’ dependency on credit became a key issue in agriculture and urban life. Each time irresponsible speculators, bankers and Wall Street got into trouble by engaging in over-speculation with no hard currency to back them up, farmers paid the price in the form of foreclosures, credit contraction, depressed crop prices and general rural poverty. In 1907, the situation was further complicated as the need for capital by farmers and brokers was at a seasonal high, as harvested crops needed to be moved to urban centers and Europe. With no central banking system in place, that is: no Federal Reserve, there was no device in place to regulate and supplement the money supply. Again, despite the relative health and prosperity of the agricultural industry, it was the farmers who had fallen victim to the ineptitude and greed of outside forces. Despite the hardships imposed on the farmer by these outside forces, agriculture continued to grow and flourish with the total acreage harvested between 1900 and 1920 increasing by 70 million acres. This steady increase under less than favorable conditions, as well as the resiliency displayed by the famers who survived constant onslaughts of natural and manmade problems, illustrate an unquantifiable aspect of farming and rural life that is admired and often romanticized by Americans. Nearing the end of his term in 1908, President Roosevelt established the “Commission on Country Life” (CCL), partially as a stance supporting his own anti-industrial/corporate leanings, and more as a response to the growing Country Life Movement (CLM), which sought to preserve and improve the agrarian lifestyle and its perceived high moral standing as a truly American institution. Roosevelt appointed Liberty Hyde Bailey of Cornell University, as the chairman of the CCL. With credentials that included the founding of the College of Agriculture at Cornell, numerous journals, and scientific publications and books that combined both social observation and scientific/technological advocacy that sold in the millions, Bailey was the authority on agriculture of the era, respected by farmers, politicians and intellectuals alike. Since the day it was published (even to the present,in oppostition to current conservative thinking) the CLC has been the object of intense criticism and even professional jealousy. In many cases this criticism, particularly in the areas of feminist issues and rural culture, fails to fully factor in the cultural norms for the era; but the fact remains that the core recommendations and suggestions brought forward by the Commission, enhanced by the atmosphere created by the Country Life Movement, opened the discussion up to the entire country. It was key to creating legislation that resulted in the establishments of institutions that not only enhanced rural life and the institution of farming, but also provided a counter to the growing power of the USDA with its strong ties to the industrial movement(s) of the day. (40)(41)(42) Benefits and Legacy of the Country Life Commission/Country Life Movement Org./Legislation/Movement Date(s) Comments American Farm Bureau 1920-present educ./mark/business Smith–Lever Act 1914-present Coop Ext. Smith Hughes Act 1917-present Vocational Edu Fed. Aid to Roads Act 1916 rural transportation Fed Rsv Banking Act 1913 rural credit Federal Farm Loan Act 1916 rural credit |

The Era Of Big Agriculure and Big Government Begins in Earnest

The Newland Reclamation Act of 1902 was the first major piece of farm legislation enacted in the new century. At the time, it provided the “missing link” that completed the agricultural colonization of virtually the entire country.As altruistic and “homesteader friendly”as this bill appeared on the surface , it was, in actuality, the culmination of over a decade of wrangling and deal making between the states and the Federal governments, the railroads (most notably, the Central Pacific and Southern Pacific), the top civil engineers of the day, land speculators, large-scale cattle concerns and mining interests. As the realities of the costs and magnitude of the “reclamation -colonization” of the West began to settle in, it became obvious that the Federal government management, government power, and ultimately government (taxpayer dollars) money would be requisite to achieve success The election of Teddy Roosevelt on a progressive-oriented platform and the arrival of Congressman Newland, who himself had been swindled as an investor in a private irrigation scheme, combined to create a coalition that culminated in the enactment of Reclamation Act of 1902 and achieved yet another step in the Federal government’s control of and involvement in agriculture. While President Roosevelt may have had many and varied reasons for his profound interest in agriculture, he ushered in an era that introduced the brought the social aspects of farming and the welfare of the farmer to the national forefront.(39) Important Issues Addressed By the Country Life Commision 1908 1.Recognition of the importance of agriculture by the general population. 2. Social and civil equality for farmers. A more equitable property tax structure for farms. 3. Equal access to water for power, transportation, and irrigation. 4. Conservation measures that preserve farmland and forests. 5. Trade and transportation regulation administered by the government. Special attention to monopolistic abuses perpetrated on farmers by railroads. 6. Government sanctioned and encouragement of rural and specialized education to keep farmers abreast of business, technological, and cultural advances and methodologies. Educational opportunities on par with urban counterparts. 7. Rural credit. 8. Immigration and the shortage of farm labor. 9. Physical and mental health of farmers including rural alcoholism. 10. The role of women on the farm. (43) |

The Country Life Movement brought the realities of the natural evolution of farming to the forefront, pointing to the need for integration between urban and rural culture and the need to understand that the romatic vision of the family farm model was not a reality. (44) (45)

|

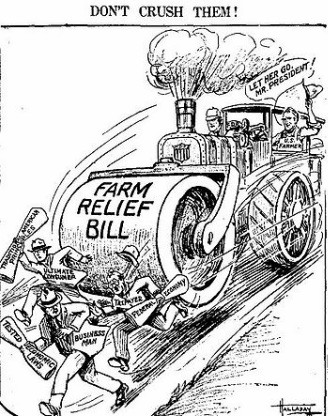

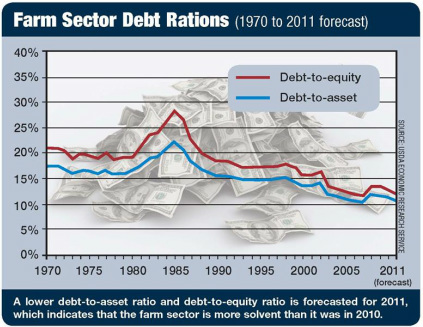

1919 to 1929 : Years of Surplus and Government Mismanagement

The country suffered a significant economic downturn just after the end of the war. This was exacerbated by the failure of the Wilson and Harding administration’s lack of contingencies to shift from a war to peace- time economy. Agricultural production geared to the war effort and fueled by increased efficiency and mechanization had created surpluses that contributed to a domestic abundance so fruitful that prices began to drop radically. Concurrent with the surpluses, and also part of the cause of these surpluses, was the fact that European farms began to return to production and Europe began to trade with Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Egypt and Canada, seeking prices lower than those of American exports. Additionally, strong lobbying by the Farm Bloc, Farm Bureau and the large meatpackers of the time including Swift and Armour, put tremendous pressure on the Federal government to successfully obtain favorable trade, credit and subsidy concessions for agri-business which in this case actually trickled down to the small farmer (initially). The benefits of legislation such as the Agricultural Credit Act of 1921, the Grain Futures Act, and the Packers and Stockyards Act, were short lived as the incentives served to encourage greater production, increasing the surplus and eventually driving down market prices Farmers who had borrowed money based on new growth and past markets found themselves struggling to service their loans. When the economy finally stabilized, market prices remained flat at the post war low until the Great Depression. (It should be noted that in terms of production and exports,1928-1929 saw generally good to excellent returns for farmers who grew wheat, realizing a surplus equal to that of its total average yearly export percentage) (46) (48) |

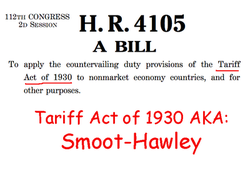

World War I and the Wilson Era Despite the interruption of the Panic of 1907, farming continued to boom in the form of all-time high prices and farm income Also, at this time, the Federal government, in reaction to market pressures brought on by unrest in Europe, domestic population growth, urban flight, perceived under-production, and a host of war related issues (security, post-war unemployment etc.) stepped up its involvement in all aspects of farm life. According to David Danbom and Wayne Rasmussen (Taking the University to the People: Seventy Five Years of the Cooperative Extension), the Wilson administration used the newly formed Extension Agent system as a key vehicle to forge government agri-policy and promote his domestic propaganda policies including anti-sedition functions and attacks on his anti-war opponents; jeopardizing the Extension’s fragile relationship with the farmers and rural communities. Agricultural production, in terms of quantity, continued to grow, though modestly, through this period holding steady at approximately $22 billion and peaking briefly in 1915 ($30 billion) and again in 1920 ($32 billion). Concerns about food shortages due to the shrinking labor pool caused by the draft and urban flight, were somewhat mitigated and alleviated by improved production techniques that included the use of hybridized and select livestock and seeds, and mechanization. Wilson’s mastery of the legislative process enabled his administration to be credited with the passage of some of the most significant farm legislation in history including the Smith-Lever Act and Federal Farm Loan Act. The immediate results of this legislation enabled the government to obtain even more control over agriculture by creating linkage between, and a dependency on, the federal and state governments by farmers through a plethora of institutions such as land-grant colleges, Federal Farm Credit and most notably, the ever expanding, USDA. The long term results of Wilson’s efforts can be seen in the precedents that were set which eventually could be used to rationalize a myriad of New Deal farm policies. These policies though still more than a decade away would have been very difficult to implement had these precedents not been set well in advance. (46)(47)(48) (49) (50) |

Like the Jefferson Embargo Act of 1803, HR4105 Illustrated the Results of Mixing Agriculture and Short-sighted Political Policy. Ultimately the Act Served To Force Importers of Us Ag Goods to Seek Other Markets Serving to Prolong the Depression's Effects on American Farmers and Consumers

Collapse, Failures, and Looking Toward the New Deal

Between 1930 and 1932, amidst foreclosures, falling commodity prices, government ineptness, drought and a plethora of crises and disasters, farmers continually adjusted in the name of survival. Some were successful and many were not. The Hoover administration did little to help agriculture beyond following the same stale and unsuccessful tactics of the past. As wheat prices fell below $1per bushel in January, the Hoover administration contemplated the Smoot-Hawley Tariff and eventually signed off on the bill in June of 1930, triggering a wave of retailtory tariffs from trading partners throughout the world that both effected farmers at that time and created an opportunity for farmers throughout the world to have access to former customers of U.S. agricultural producers.(51)

1932-36: Some Very Bad Years and Poor Decisions

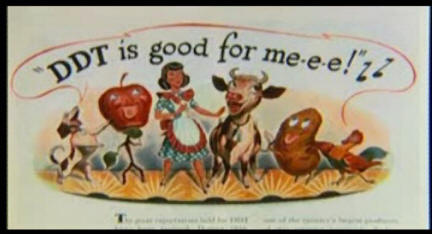

In the years after World War I, the vast acreage available in the Great Plains provided the country with an opportunity to capitalize on the devastation of European agriculture caused by the war.Again, like the "Bonanza Farm Era" this produced conditions that encouraged mass production at the expense of sound cultural practices Because of this pressure and the money available, locally-based SES (Soil Erosion Service) administrators were subject to corruption and coercion, rendering enforcement of conservation practices weak at best. The effects of the Depression served to exacerbate problems of the already difficult and complex business of farming, and while environmental conditions began to line-up in favor of the “perfect storm,” government and big business had facilitated conditions that had fostered a modified “slash and burn system” policy in search of greater profits, new employment opportunities and control over the untamed West and to some extent, the economies of the “Old World.” With uncontrolled overgrazing already weakening vast tracts of grasslands, the introduction of the steel plow and its subsequent improvements made it possible to break, turn-over and cultivate the formidable root structure and top-growth of the native sod. Coupled with a cyclical drought period, conditions were ripe for agriculture/environmental disaster " the Dust Bowl" that ensued. By the time the drought broke, temporarily in 1936, over 100 million acres of prime plains grassland were destroyed and an estimated 500 thousand Americans became jobless and may of those homeless. (53)(54)(55) |

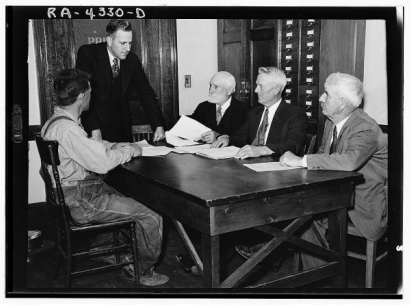

The New Deal and Agriculture New Deal was, and is still the most controversial and aggressive package of government (presidential) policy programs in the history of this country. From the outset, the New Deal gave the Executive branch unprecedented power and control over all aspects of the economy and consequently the daily lives of farmers. The Agricultural Adjustment Act was signed into law just weeks after Roosevelt took office and it immediately gave quasi-dictatorial powers to the Federal government in an effort to manipulate and pre-plan all controllable factors that affected the market and supply, done so in the interest of the country. The main crops affected were corn, wheat, cotton, rice, beans, peanuts, tobacco, and milk, but there was no sector of agriculture that was immune to government control. In its most basic and original form ( the original Act was overturned in 1936 and then re-written) the AAA worked by having farmers cut production by 30% (they were then reimbursed for their loss of product through a tax levied on both food and clothing industry). By creating an artificial balance between supply and demand, the government, in effect, raised the purchasing power of the farmer, which in turn and in theory, infused more dollars back into the manufacturing sector. After 1936, the function of the AAA and the USDA as its primary facilitator/enforcer expanded into the areas of soil conservation (in direct response to the Dust Bowl event(s), food storage/reserves and commodity-price fixing. While landowners were the main beneficiaries of these policies, sharecroppers and tenet farmers, the poorest farmers and mainstays of the Southern agricultural system of the day, not only suffered but often found themselves displaced as landlords took“their” acreage out of production to meet the requirements for receiving AAA subsidies. (52) |

Downturn, WW II and the Dawn of the Agricultural Class Structure

The original Agricultural Adjustment Act was declared unconstitutional in 1936 on the grounds that it was illegal to tax one group to pay another. The

Roosevelt administration quickly rewrote the legislation eliminating the processors’ levy and shifted the financing of the program to the general fund. It is accepted that there was a modest recovery from the depression in the early years of the Roosevelt administration (1933-1937) particularly for medium- to-large scale agriculture and related businesses.There is however, a little discussed period of downturn that resurfaced just after the start of 1937, known as ‘Roosevelt’s Depression.’ Though many of the actions that resulted from the AAA were positive, several additional acts that were implemented during the ‘Roosevelt Depression’ period, including the Resettlement Act and the Farm Security Agency, became disasters for the government. Though many of the actions that resulted from the AAA were positive, several additional acts that were implemented during the‘Roosevelt Depression’ period, including the Resettlement Act(RA) the Farm Security Agency(FSA) became disasters for the government. the highly socialist overtones of some of the actions that resulted from the RA (later to fall under the auspices of the FSA) were so controversial that they were challenged by the Supreme Court on several occasions including the “Franklin County et.al. vs. Tugwell,” which found that the RA/FSA had violated the Tenth Amendment in a number cases in which the federal government attempted to establish “Greenbelt communities and Soviet-style collective farms. “ The feedback and political ramifications of the RA/FSA, exacerbated by the downturn, marked yet another milestone in American agriculture as an institution as it further defined the hierarchy of the industry itself, identifying the real schism between the small farm and the medium-to- large, more industrial operations (ultimately coming down in favor of the latter).

As the country began to move toward war, it became clear that the federal government through the USDA, and supported by the Farm Bureau and the Grange, was going to eventually abandon its efforts at seeking equality among all farmers and concentrate on a larger more productive model for the future. Additionally, as the war effort ramped up, factory jobs became plentiful, which in turn, meant that the concern for the rural unemployed was no longer a factor. This turn of events provided the embattled administration a rationalization for distancing itself from the FSA (and eventually dissolving it in 1946) while saving face. Sociologists Jess Gilbert and Carolyn Howe, in a study of the era, evidence the fact that this shift marked the beginning of a government-induced defined class structure within the agricultural community. One of their key

observations includes, ‘. . . commercial farmers were able to beat back challenges from the agricultural underclasses and gain an enduring niche within the government.’

As the war effort gained momentum, the government began to shift its focus from control (at least temporarily) of agriculture to the facilitation of production

with a general tenor of a “hands-off” policy. Agricultural deferments were granted to farmers who produced essential crops (the interpretation of “essential” was very

liberal)The War Manpower Commission (Exec. Order 9139:1941), in terms of the agricultural sector, contained provisions that effectively left the government out of labor and wage mitigation between agribusiness and workers. Disturbingly, the order also gave the government the right to force laborers to either remain on farms, move to farms deemed important by the Commission, or face the threat of the draft; thus creating a modified slave labor class (paid but not free to move about or choose other employment). Abuse of these provisions was rampant and included such actions as forcing sharecroppers to ( illegally) sign contracts or face conscription, forcing

laborers who didn’t comply with the farm owners to be drafted, falsifying information to deceive laborers into believing that the growers represented the government , and complicity between growers and county agents in forcing laborers to accept low wages and long hours. The abuses continued until the end of the war and escalated to include less-than-subsistence wages for migrants and prisoners of war as well as the use of children and women in the fields. At war’s end, the average farm income

had risen and had in fact almost tripled due to the demands created by the war and the laissez faire type policies that were practiced at the beginning of the war. By 1947, adjustments and greater government control crept back into the industry and the die was cast, as American agriculture moved into its most productive phase ever.(56)(57)(58)(59)(60)

The original Agricultural Adjustment Act was declared unconstitutional in 1936 on the grounds that it was illegal to tax one group to pay another. The

Roosevelt administration quickly rewrote the legislation eliminating the processors’ levy and shifted the financing of the program to the general fund. It is accepted that there was a modest recovery from the depression in the early years of the Roosevelt administration (1933-1937) particularly for medium- to-large scale agriculture and related businesses.There is however, a little discussed period of downturn that resurfaced just after the start of 1937, known as ‘Roosevelt’s Depression.’ Though many of the actions that resulted from the AAA were positive, several additional acts that were implemented during the ‘Roosevelt Depression’ period, including the Resettlement Act and the Farm Security Agency, became disasters for the government. Though many of the actions that resulted from the AAA were positive, several additional acts that were implemented during the‘Roosevelt Depression’ period, including the Resettlement Act(RA) the Farm Security Agency(FSA) became disasters for the government. the highly socialist overtones of some of the actions that resulted from the RA (later to fall under the auspices of the FSA) were so controversial that they were challenged by the Supreme Court on several occasions including the “Franklin County et.al. vs. Tugwell,” which found that the RA/FSA had violated the Tenth Amendment in a number cases in which the federal government attempted to establish “Greenbelt communities and Soviet-style collective farms. “ The feedback and political ramifications of the RA/FSA, exacerbated by the downturn, marked yet another milestone in American agriculture as an institution as it further defined the hierarchy of the industry itself, identifying the real schism between the small farm and the medium-to- large, more industrial operations (ultimately coming down in favor of the latter).

As the country began to move toward war, it became clear that the federal government through the USDA, and supported by the Farm Bureau and the Grange, was going to eventually abandon its efforts at seeking equality among all farmers and concentrate on a larger more productive model for the future. Additionally, as the war effort ramped up, factory jobs became plentiful, which in turn, meant that the concern for the rural unemployed was no longer a factor. This turn of events provided the embattled administration a rationalization for distancing itself from the FSA (and eventually dissolving it in 1946) while saving face. Sociologists Jess Gilbert and Carolyn Howe, in a study of the era, evidence the fact that this shift marked the beginning of a government-induced defined class structure within the agricultural community. One of their key

observations includes, ‘. . . commercial farmers were able to beat back challenges from the agricultural underclasses and gain an enduring niche within the government.’

As the war effort gained momentum, the government began to shift its focus from control (at least temporarily) of agriculture to the facilitation of production

with a general tenor of a “hands-off” policy. Agricultural deferments were granted to farmers who produced essential crops (the interpretation of “essential” was very